We lie on a flattened cardboard box like cats stretching up to something unseen before we settle back into ourselves. For thirteen days, we have walked near each other, but not too near. There’s something in his deep-set eyes, calling me, cooling me in the deepest heat we’ve felt in this Carolina Pine forest in a decade. Or so Mama said when she dropped me off at “artsy fartsy” camp.

“Mosquitoes are gonna drink you blue, pork chop. Bottomless hot and all this rain. They’ll be biblical.”

Mama had a funny way of worrying, sure, but she wasn’t lying. Minus air-conditioning in our dorms, we emerge blinky-eyed and greasy from our bunks at night to flit and flirt on stoops, docks, grass patches on sandy earth. Between the lake, potted palms, and a general wet stink, death by skeeter seems logical. Still, I can’t take the chance of smelling like chemicals. In my head, he will remember my long braids and shoulders exhaling flower. He won’t know it’s hyacinth oil I stole from the same shop Mama buys “man-catching” candles.

“Make something pretty,” she said, arming me with seven cans of Deet, but I leave the paper bag under my bed for the duration.

Our feet now bare, we wander in grass toward each other, heel to toe, propelled like tides. John Stavros, who looks like a fifteen-year-old version of the guy from Full House, who hates it so much he twitches when you say so, who charcoals insect portraits and has the blackened fingertips to prove it, sits down next to us, but his gaze floats over us and to the stars. That’s the thing about being crammed in with other creatives –given more than a few minutes to ourselves, we turn our watery eyes skyward, like a mob of startled meercats. Some might call it fellowship. I call it someday.

“That’s Corona Borealis,” he says, prattling on to himself.

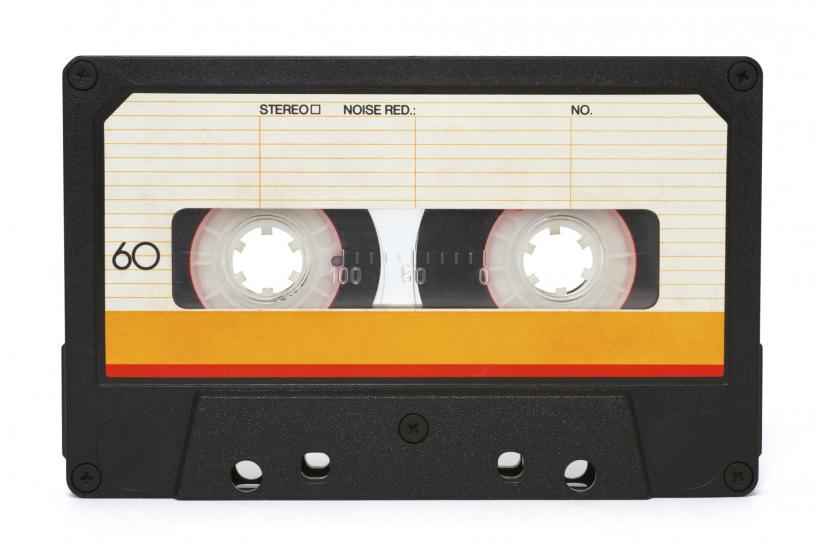

We’ve cranked the volume on my Walkman as high as it’ll go. I want him to hear Concrete Blonde and somehow, absorb all that I think and am and will be in the drumbeats and bravado of Johnette’s voice. I want to tell him about missing my drunken father and being left alone more than I care to admit. The sound of the key in the lock and the hollow rooms behind it. How there are problems with the septic tank so I can’t paint in our yard. The wall-to-wall carpet that stinks of old shower curtain. Microwave hot dogs for dinner.

But I can only say, “Listen to this. This is the acoustic version,” and will my angst into the cords, down into fibers of foam earpiece covers, into the tape rolling between us until finally, our forearms touch. We sweat against each other knowing we have to say goodbye, not caring about what we painted or produced or burned up in stagecraft. Real art comes later and after. I press stop. Stick my pinky in the plastic teeth, wind it back because my rewind button is missing.

“It’s yours, if you want it,” I say.

He hands the tape back, telling me he can’t for a swarm of reasons I don’t hear.

Twenty years pass, but there are moments of half slumber, breaths in between wine and awake, when I still look for him. Rattling seconds on a kitchen timer before bread and butter and garlic, which slows like it’s at event horizon. We are spaghettified like the astrophysicists say. Pulled apart into strings. Halved. Quartered. Thinned to particles. Someday I’ll get to the other side of this thing. The first. The conquering woman, pin-sharp, holding him in my palms. There will be no more nostalgia for burnt paper or parasites or bloodletting songs.

I purse my lips and blow him away, back into the unkempt and undisturbed from whence he came. Those smallish, stubborn bits that want to stick, to linger in my head and heart lines, become faint smudges when I rub my hands together. Maybe he only ever existed in the fire of synapses, neuron to neuron and we were only ever branching chemicals and electrical pulses. Bumps in the brain. Granule cells. So miniscule he never wrote of hanging by fingernails or my hair like the fray of Easter basket straw or the alternate universe where our doppelgängers live entwined and safe, young stars in close orbit.